%20Op%C3%A9ra%20national%20de%20Paris-min.jpg)

A rare insight into his bold, refined, and unique musical world.

%20Op%C3%A9ra%20national%20de%20Paris-min.jpg)

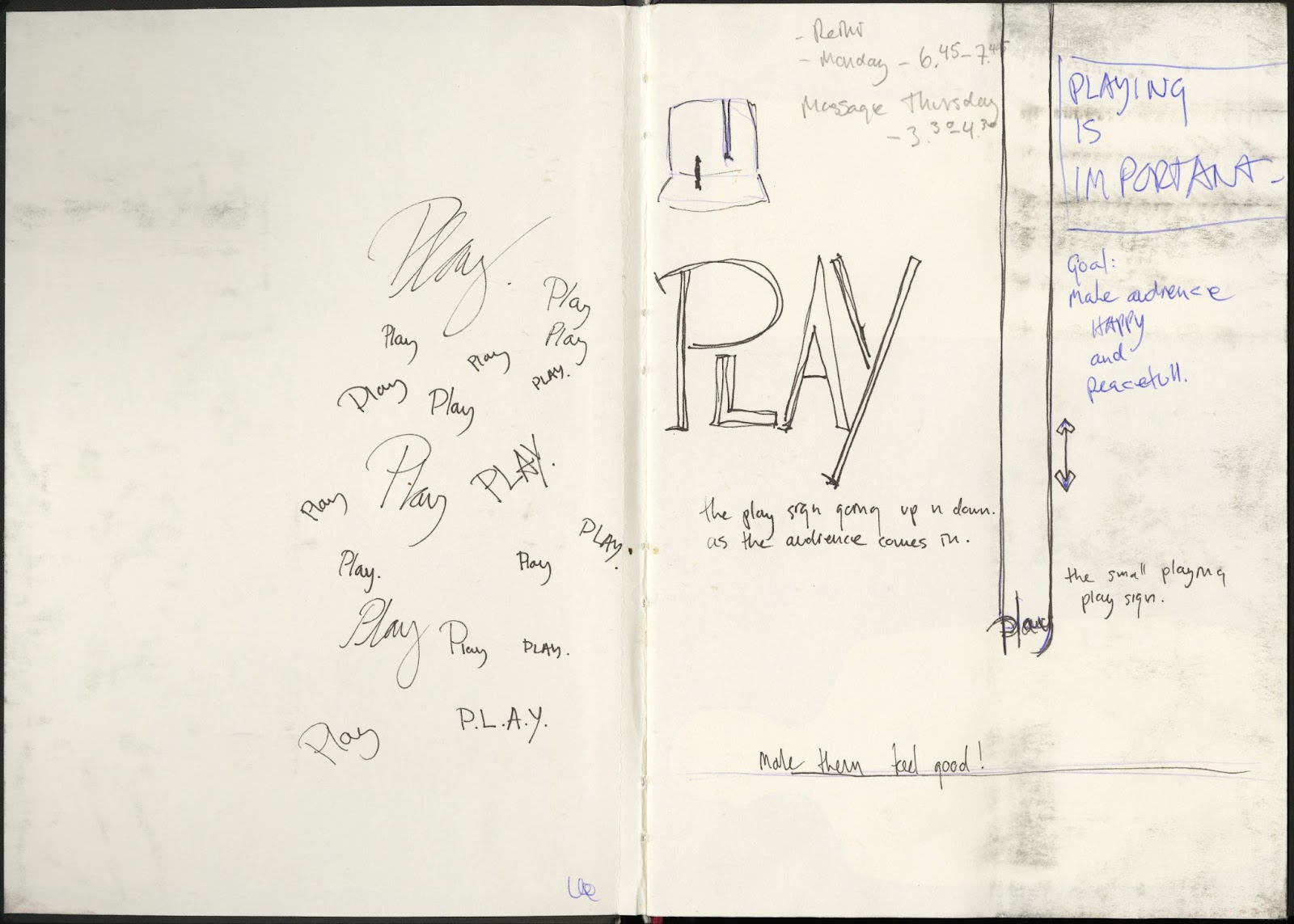

We had the honor of interviewing Mikael Karlsson, the composer of the music for the ballet Play and longtime collaborator of choreographer Alexander Ekman. He offers us a rare insight into his bold, refined, and unique musical world. Enjoy this exclusive interview.

When did you first feel deeply connected to music? What did you grow up listening to?

The first time I experienced a genuine, almost unsettling connection with music was through a film. I remember an evening spent at a friend’s house, where we watched The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, directed by Peter Greenaway. The score, composed by Michael Nyman, left a lasting impression on me – not because it conformed to any familiar musical canon, but precisely because it defied it. The music was unlike anything I had previously encountered. It relied heavily on saxophones and brass, with a sort of rhythmic insistence that felt unique. There was a boldness in its simplicity, which I found profoundly moving. From that moment on, I became utterly fascinated by Nyman’s work (track 1 and 2).

It was through this fascination that I discovered the world of classical composition. Many of the film composers I admired had been classically trained, and I felt compelled to understand the formal tools they had mastered. I wanted to acquire the means to write music with that same intensity.

In the early 2000s, I moved to New York to pursue formal studies in composition. Over the years, as my education deepened, so too did my curiosity for musical forms beyond the cinematic. While film scores remained my entry point, classical music quickly became an absorbing terrain in itself. What struck me most about New York at the time was the spirit in which music was created and shared. The city had long been home to a minimalist movement that rejected traditional hierarchies. One did not need the endorsement of a concert hall to be heard. Music could live in bars, in studios, in basements. I have always believed that it is the most healthy and promising development for classical music to be seen as music of the people, rather than a purely academic art form.

Which classical composers most influenced you during your transition into classical music?

My early immersion in classical music followed a familiar path, beginning with the great pillars of the repertoire: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven (track 3 ,4 and 5). Yet among these towering figures, it was Schubert who left an indelible mark on me. There is something profoundly moving in his music, which lies in his daring simplicity (track 6). Schubert possessed that rare gift: the ability to transform the entire emotional landscape of a piece by altering just a single note. That subtle shift, the way it unexpectedly touches the heart, is something I deeply admire (track 7).

In time, I gravitated towards the sensual richness of the French composers. Debussy (track 8), of course, and Messiaen (track 9).

Among contemporary composers, Thomas Adès stands out (track 10). His music is remarkably inventive. I also hold in high esteem several composers associated with the New York scene. Meredith Monk (track 11), for instance; Kaija Saariaho (track 12), too, has had a profound and lasting impact on my own thinking about sound.

More broadly, I sense that classical music today is undergoing a subtle but necessary metamorphosis. After decades dominated by academic modernism – often rooted in a distinctly male and Western European perspective – there is now a palpable shift. We are opening the doors to greater diversity and to the voices of women. Above all, there is a renewed emphasis on emotional resonance and on re-establishing a vital connection with audiences. That such a movement might be considered radical is, in itself, revealing. Yet it is, without doubt, a thrilling time to be making music.

When composing for dance, theatre, or film, is there something that always anchors your process?

I came to composing for dance almost by chance. At the time, it was simply one of the few professional opportunities available to me in New York. I had to make a living, and it quickly became apparent that no one was especially eager to commission sonatas. Coming out of music school, the emphasis had always been on proving one’s individuality through carefully constructed ideas. In contrast, the world of dance introduced me to a different creative model, one where collaboration is fundamental, particularly with those whose expertise lies outside my own. Alexander Ekman is a perfect example. He possesses an intuitive understanding of elements beyond my current understanding, and working with him has deepened my belief in the value of shared authorship. Rather than composing in solitude and unveiling a finished piece, the process becomes a dialogue from the outset.

Musically, I almost always start with rhythm. That instinct comes directly from my experience writing for dance. Rhythm communicates instantly. It bypasses intellectual filters, speaks directly to the body. Unlike harmony or counterpoint, which are often read through cultural or emotional lenses, rhythm is more universal. It has no fixed emotional value – it is not inherently joyful or sorrowful – but it creates the conditions in which emotion can arise.

Furthermore, it invites the listener in.That quality is essential to me. I want the music to leave space for the audience. In Play, for instance, I believe part of the piece’s power lies in its capacity to remain open – open enough for people to project their own experiences onto it. Because the structure is suggestive rather than didactic, it becomes a space of participation rather than instruction. The same is true of Alexander’s work. He constructs rhythm, pacing and imagery in such a way that the audience is drawn in without being told what to think or feel.

So whether I am writing for the stage or for the screen, two elements remain constant: rhythm and collaboration. They are my anchors. They shape how I begin, how I develop ideas, and how I make meaning.

Play blends classical forms with innovation. How do you see the balance between tradition and experimentation? Would you call yourself experimental?

The term “experimental" is often misinterpreted, particularly in the realm of music. It tends to suggest a lack of direction, as though one were simply venturing into the unknown without any clear intention. I do not identify with that definition. However, if one understands experimentation as a form of inventiveness, as the pursuit of new combinations and fresh approaches, then yes, I fully embrace that. For me, such an attitude is essential. Without it, the creative process can quickly become uninspiring. It is precisely through innovation that the work retains its vitality.

This is where collaboration becomes indispensable. We discover the piece together, and that discovery requires a constant process of mutual adjustment, of questioning. In this sense, Play is not only an artwork about playfulness, it is also a reflection of our working process. Its very structure mirrors the spirit in which it was created.

At the same time, tradition remains a vital element in our language. Alexander is a classically trained ballet dancer; his legacy lives within his body and informs his movement. Yet he has the rare ability to render tradition entirely new. Similarly, I was trained as a classical composer. I carry with me the rigour and discipline of that heritage.

What makes your long-standing collaboration with Alexander Ekman so lasting and creatively rich?

Our collaboration has endured, I believe, because it was first and foremost rooted in friendship. When Alexander came to New York to create a piece, we had no initial intention of working together. We simply became friends, quite naturally. That human connection laid the foundation for everything that followed.

Over the years, through repeated collaborations, we have developed an instinctive understanding of one another. There is no need to start from scratch each time we begin a new project. Familiarity allows us to bypass much of the preparatory dialogue, and to begin almost immediately in the realm of creation. In our case, the sonic world of Play is very much the result of this long-standing dialogue and mutual respect. Although we each work with other artists, myself with other choreographers, and Alexander with other composers, this particular collaboration holds a special place for me. He was, in fact, one of the very first choreographers I worked with. At the time, I had no idea I was collaborating with one of the most extraordinary artists in the field. Only later did I realise the full extent of his brilliance. In many ways, I was simply lucky that he was the one with whom I started.

How do you and Alexander Ekman keep challenging each other creatively?

The essence of our creative relationship rests on a shared principle: no idea is immediately rejected. This approach resembles, in spirit at least, the foundations of improvisational theatre. Although I have never practised that discipline myself, I recognise in it a vital lesson. The rule is simple: one must never say “this will not work.” We apply this principle rigorously in our process.

Very often, the most unpromising idea turns out to be the most fertile. The true challenge, then, is to remain open for as long as possible, to allow space for surprise. In our case, this means accepting the need to generate an abundance of material. When we work together, I often write music for several pieces. That generosity is necessary, because it allows us to follow every thread before deciding which to keep. Before rehearsals begin, we look at everything with a clear and critical eye. Much of what we have created is set aside. But none of that would be possible without the initial willingness to embrace uncertainty.

What makes this partnership all the more dynamic is that we both challenge one another. In our case, it means to remain open. We experiment, we take risks, and something new always arises from that exchange. It requires patience, mutual respect, and a genuine curiosity about where things might lead. That shared discipline sustains the vitality of our work, and allows it to keep evolving.

When you began composing Play with Alexander Ekman, where did the process start?

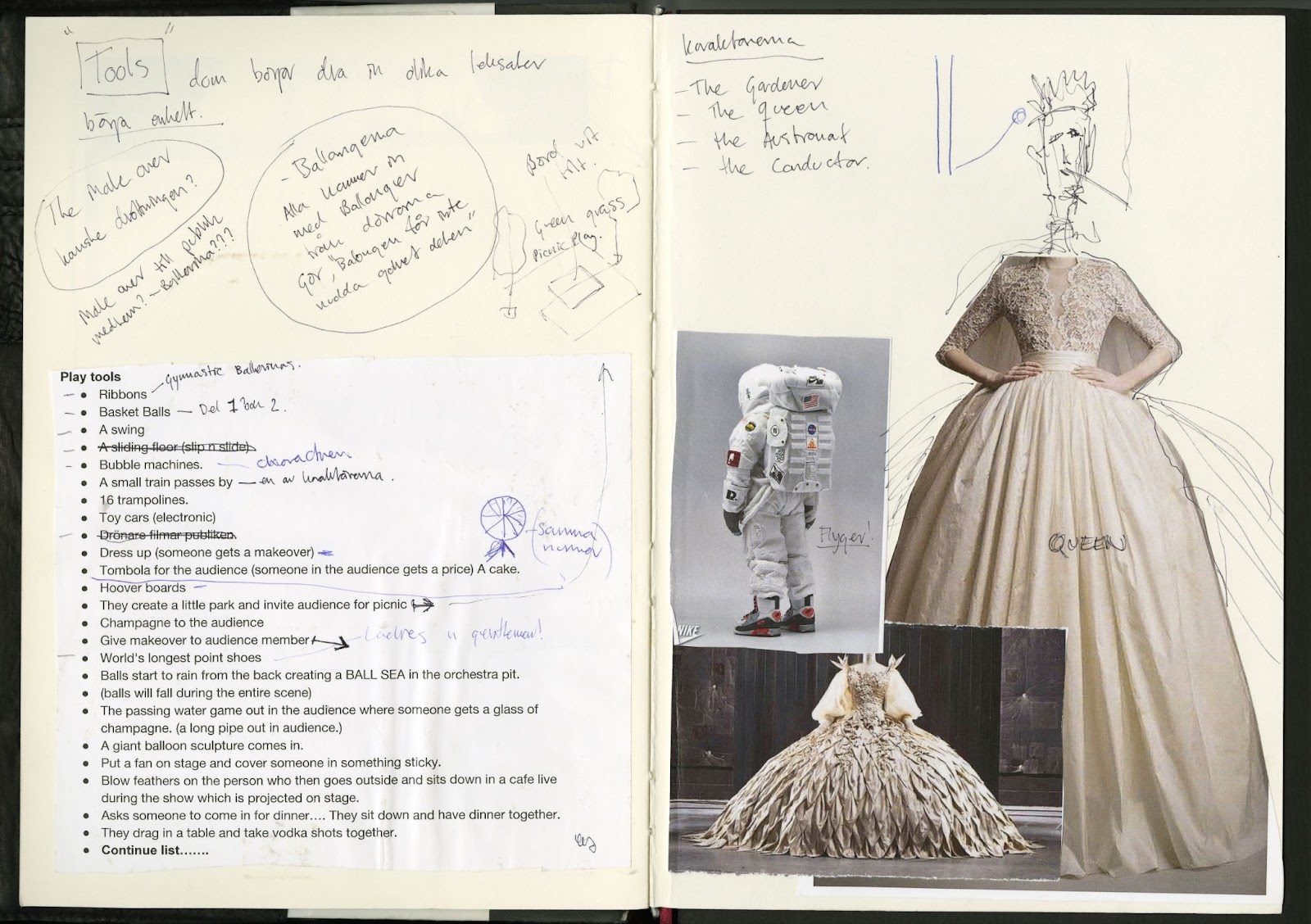

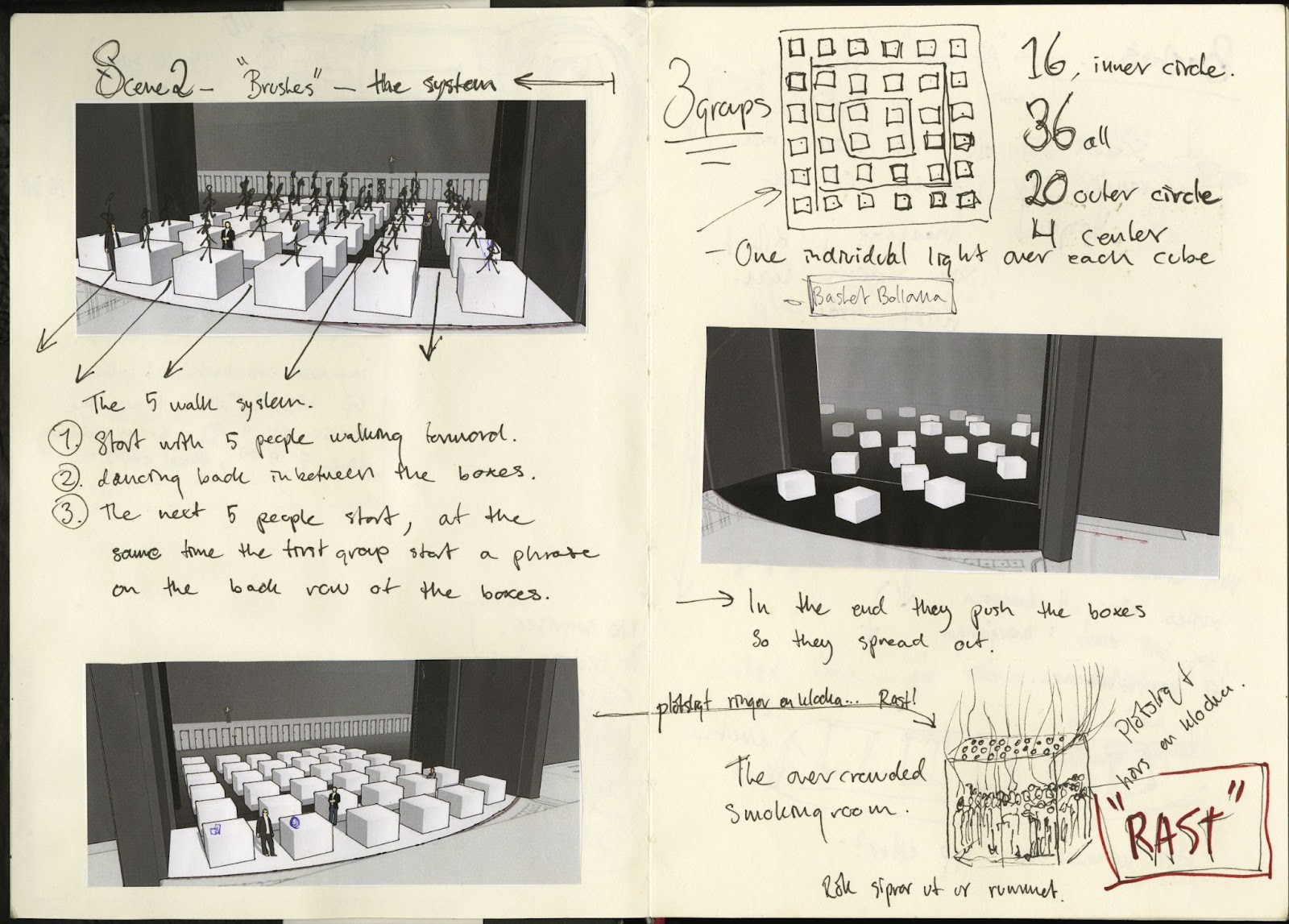

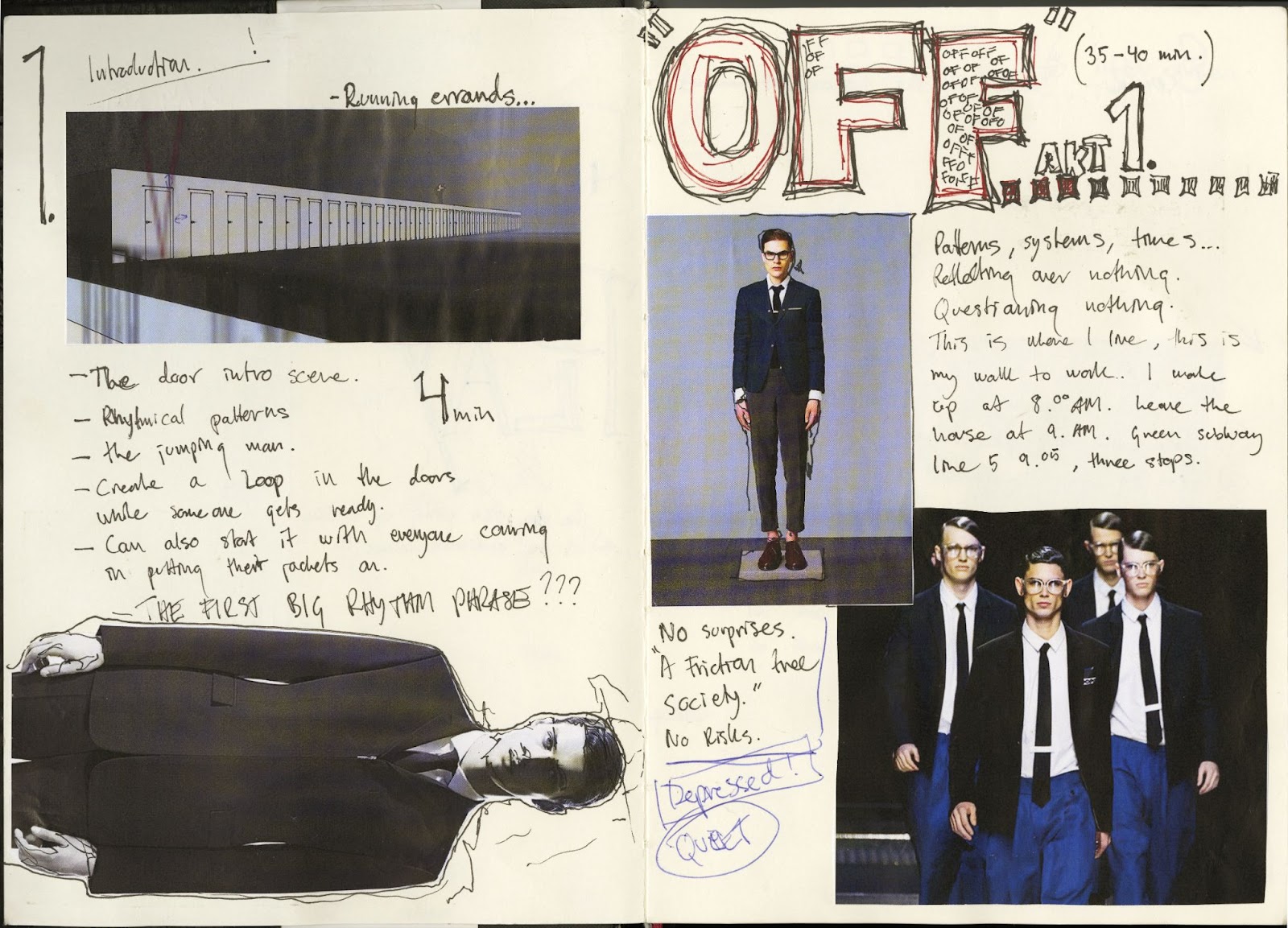

We rarely have a precise idea of what the final piece will become. The creative process for Play began, as it often does with Alexander, from a series of striking visual concepts. His aesthetic sensibility is extraordinary, and he often produces imagery that I find profoundly affecting, even though I cannot always articulate why. My role, then, is to compose music that resonates with those images. For instance, regarding Play, he showed me early images of large suspended cubes, which he had envisioned from the very beginning. He also described the idea of balls falling from the ceiling – another bold scenographic element that he knew would appear at some point in the production. These moments serve as fixed visual anchors, and they become early reference points for the composition. In this case, we knew from the outset that there would be a scene of pure excess and abandon. That sense of exuberance later took shape as the climax of the first act, precisely when the balls begin to fall. Once that central scene had been identified, we could approach the rest of the work with a certain clarity.

At the same time, I had my own musical intentions. I had long wanted to compose for saxophones, partly due to my admiration for the music of Michael Nyman (track 14). Around that period, I also encountered a viral video of the American singer Callie Day, performing a rehearsal rendition of Hear My Prayer in a gospel setting. Her voice left me completely astonished. The beauty, range and expressive power of her singing were unlike anything I had heard. I shared it with Alexander and asked whether we might be able to invite her to participate in the piece. His response was enthusiastic. Once Callie Day became part of the project, it became evident that we would need to write material specifically for her. I began composing songs, loosely connected to the overarching themes of the piece.

Then, I also came across a recording of a speech by Alan Watts, a popular philosopher whose reflections I had long appreciated. In it, he spoke about the importance of presence, of learning to be in the moment, and of the idea that life, ultimately, is a form of play. His words resonated so precisely with the conceptual framework of the production that I sent the clip to Alexander. He responded immediately, suggesting we incorporate the recording directly into the piece.

With these elements in place – the scenographic visions, the instrumental ideas, Callie Day’s presence, and the Alan Watts recording – we entered the next phase of our process. Alexander came to my studio, and over the course of a week and a half, we worked closely, sketching ideas and exchanging impressions. I would play him fragments, textures, rhythmic patterns, and he would respond intuitively. "I like this," he might say, or "This doesn’t quite land," and so we built the material collaboratively, allowing ideas to unfold freely. That initial period is essential. In truth, one can only sustain real creative intensity for four or five hours a day before ideas begin to lose their vitality. Within that rhythm, however, we managed to produce nearly eighty musical sketches. Once that phase was complete, Alexander returned to his own space to continue developing the production, while I remained in the studio to expand the selected sketches into longer, fully formed musical scenes.

This is the shape the process often takes with us. It is a conversation built on mutual trust and responsiveness, where the piece gradually reveals itself through shared instinct.

How has working with Alexander Ekman, who blends classical technique with innovation, influenced your approach to narrative and composition?

One of the most significant lessons I have learned from working with Alexander is that narrative need not follow a linear or literal path. While his productions are always grounded in a central theme, the individual scenes are rarely bound by traditional storytelling. Rather than unfolding as a sequence of plot points, they operate through atmosphere, contrast, and visual impact. This has reshaped the way I think about structure and intention in music.

For example, I had to learn how to integrate humour into my work – something rarely addressed in classical training. With Alexander, I came to understand that playfulness can be a powerful dramatic tool. Sometimes, silliness is not a distraction from meaning, but its unexpected companion.

A clear instance of this can be found in the second act of Play, particularly in the scene where the recording of Alan Watts’s voice is introduced. That passage begins with a rather garish sample of barbershop harmonies, which we had discovered in a sound library. Left to my own devices, I would never have chosen them. But Alexander simply remarked, “That’s funny,” and encouraged me to use them. The result is a juxtaposition of absurdity and mundanity: the music, light-hearted and kitsch, plays over a grey, repetitive office scene. The dissonance between sound and image creates a peculiar tension, forcing the audience to confront the contrast and, perhaps, to question it. We do not dictate interpretation; rather, we invite it. I am reminded of a remark by Hans Zimmer, the film composer, who once said: “I don’t want to tell the audience what to feel. I just want to open the door so they can feel something.” That sentiment resonates deeply with me. In other words, a scene does not need to instruct the audience on what to think or feel. Every person who enters a theatre brings the texture of their life with them – some with grief, others with hope, anxiety, or indifference. In fact, the most powerful experiences often arise when the work leaves room for the viewer’s own projections. Our pieces function best when they remain open, when they allow each spectator to bring their personal joys, sorrows, expectations, and fatigue into the encounter. The result is a collective emotional field, yet one that is profoundly individual in its reception.

Alexander understands this with a rare precision. His visual worlds are never static; they are richly detailed, always in motion, and aesthetically captivating. That is why audiences surrender to his pieces. They are never lectured. Instead, they are entertained, and while they are entertained, something deeper unfolds, quietly, almost imperceptibly. That subtle emotional aftertaste, which lingers long after the performance ends, is what we strive to achieve. And Alexander has an exceptional gift for creating that experience. He leads the audience to feel something without ever telling them what it must be.

Play has been performed over sixty times at the Paris Opera and will soon debut in Tokyo. How does it feel to have your music resonate worldwide?

Last December alone, Play was performed twenty-three times at the Paris Opera, meaning that over forty thousand people experienced the piece during that run. The scale of it is overwhelming, and emotionally, it remains just out of reach. The knowledge that so many people are taking time out of their lives to attend a performance of this work is profoundly moving. It reminds me that no performance should ever be taken for granted. We have a responsibility to honour their presence with a ballet that is fully deserving of their time and attention.

Looking ahead to Tokyo, I will travel to Japan to rehearse with the orchestra and the sound department, and the sense of wonder only deepens. There is a sort of magic in that prospect - the idea that a work born out of our particular collaboration in Europe might resonate in another cultural context, with another public. All we can do is offer the most faithful version of the piece that has found such a strong response in Paris, and hope that it speaks just as clearly in this new setting.

We’ve talked about innovation and trust in the creative process. How do you keep your curiosity and sense of wonder alive as a composer?

Curiosity, for me, emerges naturally from the very act of composing. Whenever I embark upon a new work, I am utterly unaware of its eventual form or character. This state of not knowing does not provoke anxiety but instead ignites genuine excitement. I approach each project as though I were entering uncharted territory, free to explore and to discover. In this way, composition becomes akin to a form of creative play, reminiscent of a child’s exploration, where every path leads to new possibilities.

In my experience, the most thrilling moment does not arrive at the premiere. The moment I treasure occurs much earlier, during rehearsal. After many hours of work, there comes a point when the music finally feels alive and charged with promise. It is impossible to know then whether the piece will succeed, but one senses that it has ceased being merely an idea and has begun to take on its own energy. That instant of emergence, when potential becomes palpable, is what keeps me returning to the studio. I remain ever eager to discover what will come next.

Any upcoming projects you’re excited to share?

Alexander and I are currently developing a new piece for orchestra and film. As always with our collaborations, I expect it will evolve into something entirely its own – unexpected, challenging, and full of discovery.

In parallel, I have just completed a work for the Swedish Radio Orchestra and Choir, in collaboration with the singer Anna von Hausswolff. We have incorporated electronics, spatialised sound, and surround techniques in the piece to create a sonic landscape that I believe is unlike anything the ensemble has performed before. It is entirely new for me, and precisely for that reason, it is profoundly exciting.

More broadly, I have also been devoting myself increasingly to opera. As an art form, opera carries with it a considerable weight of tradition and convention. And yet, in many ways, it remains curiously unresolved. I often feel that it struggles to connect fully with contemporary audiences. The need to reimagine what opera might become, is a challenge that motivates me deeply. There is a kind of creative urgency in working within a form that requires transformation.

Do you listen to opera? How do you see the connection between opera and dance?

In truth, I listen to opera very rarely. I suspect this is the case for most people, though it is not something the opera world likes to acknowledge.

What surprises me, time and again, is how little attention is paid to the full theatrical experience. Opera is still often conceived as the union of musical score and libretto, as though the rest were mere ornament (track 21). But the direction, the movement, the lighting, the video work, the set design, the costumes, these are not peripheral. They are essential. If any one of them lacks vitality or purpose, the result is a diminished experience. When opera is unsuccessful, it can be almost unendurable. The same, in my experience, is true of dance. Both forms are unforgiving when they fall short.

Collaboration is central to my approach. Opera is a collective undertaking (track 22). Its success depends on the excellence of every craft and workshop involved. That is the spirit I try to bring into the opera house. I work with singers in the same way I have long worked with dancers. I do not simply deliver a finished score and say, “Here is the opera.” I show it to them, we experiment together, and we revise the work as a shared act. It becomes a living process rather than a finished product.

Finally, I see very direct bridges between opera and dance. Much of what I have learned through my work in dance now informs the way I approach opera. One of the most important lessons is the necessity of momentum. A scene must move. Too often, opera suffers from stasis. It unfolds with a kind of reverence for slowness, which can become suffocating. I strive to counter that. I want the music to serve the drama, and not the other way around.

If you could score the soundtrack to any film?

It would be Apocalypse Now by Francis Ford Coppola.

I should say at once that I already love the film exactly as it is. It does not require a new score, nor would I presume to improve upon it. Yet it remains, for me, a fascinating case. It combines moments of the grotesque, the absurd and the sublime within a single narrative. The film becomes increasingly hallucinatory until, by the end, one is no longer sure what is real and what is imagined. The way it employs existing tracks such as The Ride of the Valkyries (track 24), or The Doors is brilliant and deliberately provocative. It feels excessive and that’s precisely what makes it powerful. I believe it would be thrilling to imagine one nonetheless!

If you were an instrument?

I would be either a viola or a bass clarinet, each for different reasons.

The viola, as a string instrument, exists in the middle register. It plays an essential role in the harmonic structure of music, yet rarely draws attention to itself. It seldom receives the grand solos. Those are generally reserved for the violins or cellos. And yet, the viola’s sound possesses an intimacy and warmth that I find profoundly moving. I identify with its presence in the ensemble: not seeking the spotlight, but standing just beside it, supporting others, like a tailor adjusting a garment so that someone else may shine.

The bass clarinet, on the other hand, is an instrument of extraordinary character. Its sound is dark, ancient, and oddly pure. I could listen to it endlessly.

If you were a tempo?

I would be 104 beats per minute.

It sits just below what one would consider energetic. It is not quite fast, and not quite slow. Over time, I have come to feel that this tempo contains a sort of hidden power. When one wants to create excitement, the instinct is to accelerate. But when one slows things down, the music begins to breathe differently. It no longer runs; it strides. It acquires weight and presence. Moreover, 104 beats per minute resists categorisation. It is neither overtly dramatic nor entirely serene. It hovers in a space of possibility, as though something is about to unfold but has not yet declared its nature. I find that ambiguity deeply compelling.